Credit card delinquencies have started to rise recently after falling during the pandemic. For creditors, the final recourse to collect an unpaid debt is typically to sue the consumer in state civil courts. If the creditor wins the suit, the resulting “civil judgment” will often give the creditor the right to garnish wages or seize bank accounts, homes, cars, or other property to pay off the debt. Defendants in debt collection suits usually do not have counsel. Default judgments, in which the court finds for the creditor without ever hearing from the defendant, are common.

Civil judgments are public. These dry court records tell tales of people in financial distress. For example, John was sued for about $1,400 last year.1 After a default judgment allowing wage garnishment, the court ordered his grocery store employer to start garnishing some of his $16 an hour wage. It appears he left his job or was fired several months later. Because the creditor may not have collected much money, he may remain at risk of wage garnishment at his next job until the judgment is paid in full.

Despite their importance in the lives of struggling consumers, understanding civil judgments has been hampered by limited data. Our new working paper fills this gap by using credit bureau data to study civil judgments and their relationship to wage garnishment laws. In this blog post, we show that civil judgments are both common and unequally distributed.

New facts about civil judgments

Most research studying the interaction between indebted consumers and the court system has focused on the effects of bankruptcy law. Bankruptcy law is intended to protect consumers from the consequences of being in debt. Civil judgments, on the other hand, protect creditors and have negative economic consequences for consumers.

The consumers experiencing bankruptcy also differ in important ways from consumers affected by civil judgments. Bankruptcy is primarily used by people with assets. In fact, as we show in the working paper, people who ultimately file for bankruptcy are more likely to have a mortgage or auto loan than the average consumer. In contrast, people who ultimately have a civil judgment filed against them are much less likely to have a mortgage or auto loan than the average consumer.

Our report establishes three new facts about civil judgments that show that civil judgments are both common and unequally distributed:

- Civil judgments are about twice as common as bankruptcies.

- Civil judgments are 20 times more common in some states than others.

- Civil judgments are more concentrated in areas with a higher percentage of Black residents even after adjusting for the rate of unpaid debts.

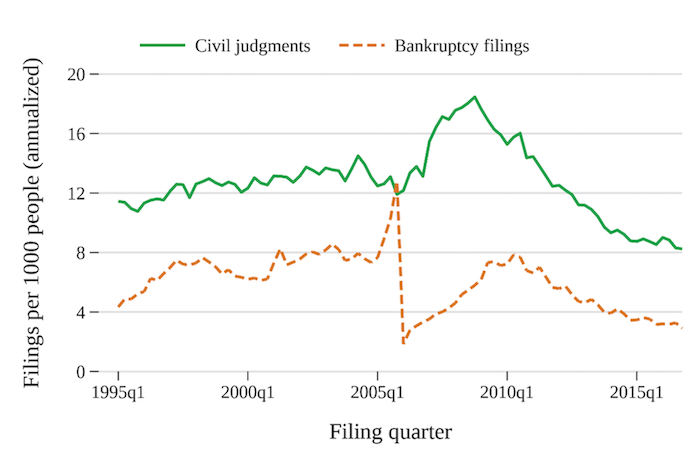

Civil judgments are more common than bankruptcies

Bankruptcy filings are sometimes used as a measure of consumers struggling with debts, but struggling consumers are more likely to be sued in court than to seek bankruptcy protection. Figure 1 shows the number of civil judgments and bankruptcies per 1,000 people over time. The incidence of civil judgments increased steadily from 1995 to 2006 when 13.1 civil judgments were obtained per 1,000 people. Judgments increased rapidly during the next two years, reaching a peak of 18.5 civil judgments per 1,000 people by the last quarter of 2008. Since then, the incidence of civil judgments has been declining steadily to 8.6 civil judgments per 1,000 people by 2016.2

Figure 1: Civil judgments and bankruptcy filings per 1000 people.

By comparison, bankruptcy filings are generally about half as common as civil judgments, although they are not entirely comparable because bankruptcies typically cover several debts and larger amounts. Unlike civil judgments, bankruptcy filings occur in federal, not state courts, and are governed by federal law. The big spike in bankruptcy filings in 2005, followed by the drop, is because of the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA), which made bankruptcy more costly to file.

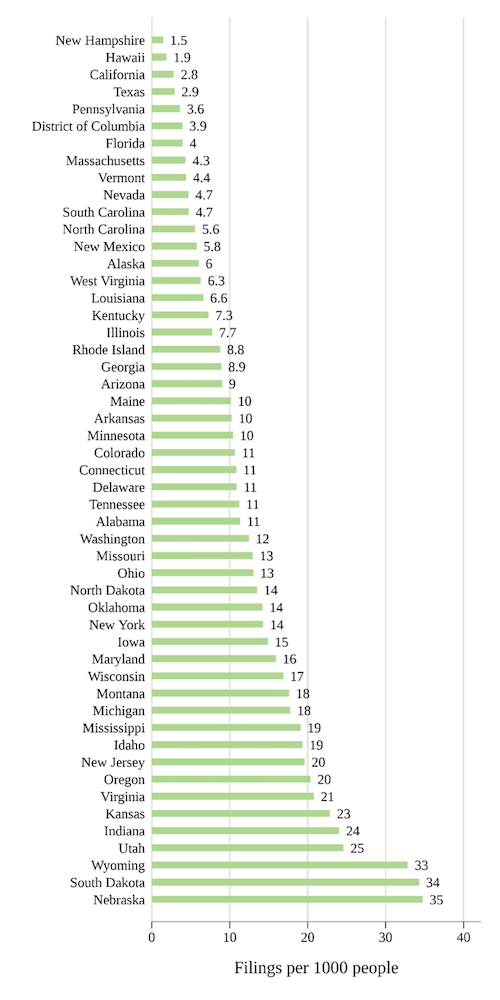

Civil judgments are more common in some states than others

Civil judgments are governed by state law, so it is not a surprise that their rates vary across states. What is a surprise is just how much they vary. Figure 2 shows the civil judgments per 1,000 people in each state. The states with the highest incidence in 2012—Nebraska and South Dakota—have about 20 times the civil judgments per capita than those with the lowest incidence—New Hampshire and Hawaii.

Figure 2: Civil judgments per 1000 people by state in 2012.

Why are civil judgments so much higher in some states than others? States approach debt collection very differently, which affects the incentives for creditors to sue consumers. One of the biggest differences is how much of someone’s wages can be garnished. Some states, such as Pennsylvania and Texas, generally prohibit wage garnishment for consumer debts (although wage garnishment is allowed for child support), while others only protect the federally required minimum amount from garnishment. There are also differences across states in how easy and cheap it is to file a suit. The costs of filing vary, for example, with attorney salaries in a state, the court fees in a state, and whether a state allows out-of-state counsel or electronic filing.

We find that states with more wage garnishment protections have fewer civil judgments. Further, we find that states with lower filing costs have far more civil judgments.

To study these effects, we build the most comprehensive database of wage garnishment across states and time in the working paper . Many things differ between states, so isolating the impact of wage garnishments requires more than just comparing New Hampshire to Nebraska. To deal with this problem, we look only at changes in wage garnishment rules within states over time and how those changes impact civil judgments and access to credit. We find that as states protect more wages, the number of civil judgments declines. But increasing wage garnishment protections also reduces credit card limits.

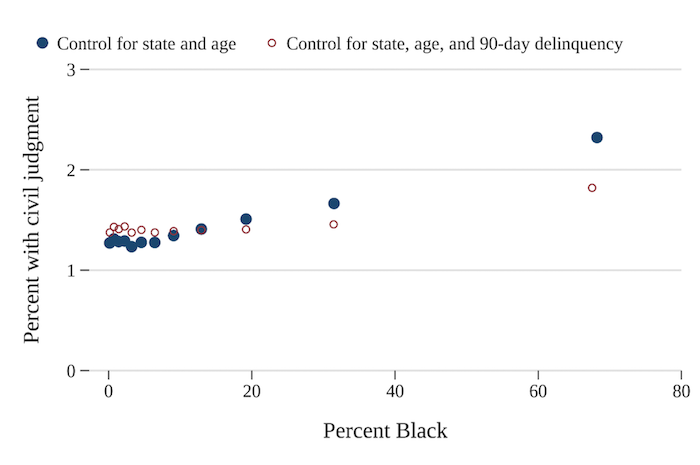

Civil judgments are more common in areas with a high percentage of Black residents

Who gets a civil judgment? As an area’s share of Black residents increases, the incidence of civil judgments also goes up. Figure 3 shows this rise. In Figure 3, we look only at differences within states. As Figure 2 shows, looking across the whole nation would conflate differences by the share of Black residents within states and differences in the share of Black residents across states with very different incidence of civil judgments.

Figure 3: Civil judgment incidence compared to the percentage of Black residents by census tracts in 2012. The dots are a “binned scatter” representing the average for an equal number of census tracts. The filled circles control for state and age, the empty circles control for state, age, and the percentage of 90-day delinquencies.

Even comparing across areas with the same delinquency rates, areas with a higher share of Black residents have more civil judgments. The open circles in Figure 3 show that the increase with race is still there even when we control for the frequency of over 90-day delinquencies. Smaller case studies have found something similar.

Civil judgments are common and not evenly distributed

When we think about how indebted consumers interact with the court system, it’s easy to focus on how bankruptcy law can protect consumers from their creditors. But civil judgments are more common and these court orders can have large negative implications for consumers including wage garnishment and asset seizures. Yet civil judgments are not evenly distributed. People in some states and living in high-percentage Black areas are more likely to have one. This uneven distribution matters, because, as John’s case illustrates, civil judgments can have a profound impact on people’s lives.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Links or citations in this post do not constitute an endorsement by the Bureau.

Footnotes

- John is not his real name, but the case and details are real and public. We do not link to the public record to protect “John’s” privacy.

- We end our reporting in 2016 because civil judgments were removed from credit bureau records in 2017.